Inflight Magazine of Brussels Airlines

Welcome to the Inflight Magazine of Brussels Airlines

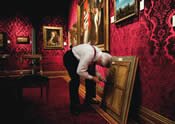

At what price art?

Images Loraine Bodewes, Corbis

The art market has taken a hammering during one of Europe’s fiercest recessions, but with confidence now returning among buyers, the good times might be back. Claire Wrathall makes a bid for the details

When an anonymous telephone bidder paid €72m for Giacometti’s sculpture L’homme qui marche I at Sotheby’s in February, the art world breathed a collective sigh of relief. This wasn’t just the most anyone had ever spent on a work of art. It was a sign the market had turned a corner – the worst of the recession was over.

When an anonymous telephone bidder paid €72m for Giacometti’s sculpture L’homme qui marche I at Sotheby’s in February, the art world breathed a collective sigh of relief. This wasn’t just the most anyone had ever spent on a work of art. It was a sign the market had turned a corner – the worst of the recession was over.

A week later, and the results of the contemporary sale at the same London auction house (the centre of the European art market, and second only to New York in the world) were almost enough to convince the industry that the good times were back. The atmosphere in the packed saleroom was electric, with bids rising in increments of £10,000 and applause breaking out when the hammer came down on the most spectacular sales – the €4.5m paid by a private collector for Willem de Kooning’s Untitled XIV (1983), for example. “It was amazing,” says Sophie Camu, a Belgian-born but London-based art consultant and formerly a director of Sotheby’s Impressionist & Modern Art department in Paris. “Everything was going through the roof, fetching five to 10 times its estimate.” That evening, 21 new artist records were set, and more than €61m was spent. As Cheyenne Westphal, Sotheby’s European chairman of contemporary art, said afterwards: “The strong prices we achieved this evening are a clear sign of renewed confidence… affirmation of the market’s hunger for fresh-to-the-market works with exceptional provenance.”

Camu, too, is hopeful that things are improving, and not just for “the blockbusters and really high-value works. Even the lower-value works were selling terribly well, which is encouraging for the market in general.” Take the untitled acrylic abstract by Sam Francis, for example: estimated to fetch €6000, it realised €12000. Camu attributes this to a new confidence among buyers, but also sellers. She says that, ‘distress sales’ apart (where a vendor is compelled to sell by other losses), “no one really wanted to sell last year, so it was difficult to get property consigned. That sellers now have the confidence to put property up for auction is really a sign that the art world is doing well again.”

Camu, too, is hopeful that things are improving, and not just for “the blockbusters and really high-value works. Even the lower-value works were selling terribly well, which is encouraging for the market in general.” Take the untitled acrylic abstract by Sam Francis, for example: estimated to fetch €6000, it realised €12000. Camu attributes this to a new confidence among buyers, but also sellers. She says that, ‘distress sales’ apart (where a vendor is compelled to sell by other losses), “no one really wanted to sell last year, so it was difficult to get property consigned. That sellers now have the confidence to put property up for auction is really a sign that the art world is doing well again.”

Healthy figures

This comes as a relief after what has been a challenging two years for art dealers. Each year, TEFAF Maastricht, the largest international fine art fair in the world, commissions a report on the international art market – and its latest findings make for salutary reading. “Although some sectors of the international art market have undoubtedly been affected by the economic recession, others have fared much better than might have been expected,” says economist Dr Clare McAndrew, the author of the report. “Total sales in 2009 were well down on the boom year of 2007, but they still exceeded any year in the art market’s history before 2006. In 2008, total sales in the global market for fine and decorative art reached just over €42.2bn, down more than 12% from its peak in 2007 of €48.1bn.”

In 2009, sales slipped further, but they nevertheless amounted to €31.3bn, while less volatile sectors – such as old masters, jewellery and silver – saw rises. And last year is held to be the best yet for Chinese art, with €2.4bn-worth sold. If contemporary art appeared badly hit – which it was – then it’s worth remembering that the market for it had risen tenfold inside a decade, peaking in 2008, when cumulative sales at auction totalled €670m.

In 2009, sales slipped further, but they nevertheless amounted to €31.3bn, while less volatile sectors – such as old masters, jewellery and silver – saw rises. And last year is held to be the best yet for Chinese art, with €2.4bn-worth sold. If contemporary art appeared badly hit – which it was – then it’s worth remembering that the market for it had risen tenfold inside a decade, peaking in 2008, when cumulative sales at auction totalled €670m.

McAndrew’s findings also chime with Camu’s observation that it’s the less exalted end of the market that’s holding strong. “Despite multi-million dollar lots receiving most of the media attention, the majority of art trading now takes place at the lower end of the market, regardless of the sector,” she says. In terms of prices, the middle market has suffered worst. If you have millions, the flight to quality tends to endure in times of economic uncertainty. But equally, in times of low interest rates and stock-market volatility, where better to invest a few thousand euros than in something that generates pleasure as well as at least a potential for growth?

Auctions off?

Perhaps inevitably, this has heralded a change in the way people buy art. Auctions may make the headlines, but they actually now account for just 45% of global art sales. The rest is sold through dealers. As one senior American hedge-fund manager with a collection of museum-quality 16thand 17th-century Dutch and Flemish paintings confided, the downsides of buying at auction are: “First, you’re competing with the whole world. And second, even if you didn’t care about the price, anyone who knows anything about the art world will know where you found it and what you paid for it.”

Perhaps inevitably, this has heralded a change in the way people buy art. Auctions may make the headlines, but they actually now account for just 45% of global art sales. The rest is sold through dealers. As one senior American hedge-fund manager with a collection of museum-quality 16thand 17th-century Dutch and Flemish paintings confided, the downsides of buying at auction are: “First, you’re competing with the whole world. And second, even if you didn’t care about the price, anyone who knows anything about the art world will know where you found it and what you paid for it.”

But perhaps the best reason to buy through a dealer is just how easy it is compared with auctions, which, though thrilling, can be intimidating for the inexperienced. What with the adrenaline rush brought on by bidding, you may end up paying more than the piece is worth (the buyer’s premium at Sotheby’s and Christie’s is 25% of the hammer price plus sales tax). And even if the auction houses don’t disclose buyers’ names, lot details and prices paid are published. As a vendor, meanwhile, you may not achieve a sale at all if something doesn’t reach its reserve. As London gallery owner Andrew Clayton-Payne says, “If I don’t manage to sell something, at least no one has seen it fail to sell, and the owner can do something else with it.” It won’t have been ‘burnt’: the word the art world uses to describe a work whose value has been tarnished by over-exposure.

Fair deals

Of course, private galleries can also be intimidating, which is why dealers increasingly rely on fairs for the bulk of their business. Here, their art is likely to be seen by a far greater concentration of people than might wander in to a gallery. Another advantage, from a casual browser’s perspective, is that you’re less likely to fall under the gimlet eye of the ‘gallerina’ – a gallery attendant possessed of too much attitude – as she’ll probably be too busy chatting up the museum curators and senior dealers.

Of course, private galleries can also be intimidating, which is why dealers increasingly rely on fairs for the bulk of their business. Here, their art is likely to be seen by a far greater concentration of people than might wander in to a gallery. Another advantage, from a casual browser’s perspective, is that you’re less likely to fall under the gimlet eye of the ‘gallerina’ – a gallery attendant possessed of too much attitude – as she’ll probably be too busy chatting up the museum curators and senior dealers.

There are more than 200 international art fairs each year, offering work across all genres. Contemporary fairs include this month’s artbrussels (23-26 April, www.artbrussels.be), ViennaFair (6 to 9 May, www.viennafair.at) and Art Athina (13-16 May, www.art-athina.gr), while fine art and antiques are on show at Europ’Art in Geneva (28 April – 2 May, www.europart.ch) and the inaugural edition of the London International Art Fair (4-13 June, www.lifaf.com). Art Basel (16-20 June, www.artbasel.com) and Design Miami/Basel (15-19 June, www.designmiami.com) may be the two unmissable dates in any serious collector’s summer schedule, but there’s barely a week in the year without a fair somewhere.

What’s more, art fairs worth attending whether you’re there to buy or just to look, as viewing art in a commercial context is entirely different from a gallery. If you see something you respond to, gaze long and hard – it may be the last time it’s seen by the public. Better yet, buy it. As J Paul Getty said: “Fine art is the finest investment.” The markets may fluctuate, but a thing of beauty really is a joy forever.

FR L’art, mais à quel prix?

En Europe, le marché de l’art a été quelque peu ébranlé au plus fort de la récession, mais progressivement la confiance revient parmi les acheteurs : l’optimisme des bonnes années pourrait bientôt refaire surface. Claire Wrathall analyse les signes de cette reprise.

Lorsque chez Sotheby à Londres, en février dernier, un enchérisseur anonyme a mis sur la table 72m d’€ pour L’homme qui marche I de Giacometti, le monde de l’art a poussé un soupir de soulagement. Lorsqu’on y ajoute les résultats impressionnants des ventes contemporaines de Sotheby, pour plus de 61m d’€, cette transaction a été regardée comme un signe indéniable du redémarrage des affaires.

Le rapport annuel de la TEFAF, la plus grande foire d’art et d’antiquités à l’échelle internationale, donne encore plus de raisons de se laisser porter par la vague d’optimisme. Les chiffres montrent que si certains segments du marché ont été affectés par la crise, d’autres ont mieux performé que prévu. C’est le cas des tableaux de maîtres, des bijoux et surtout de l’art chinois. Et fait important, la base du marché – là où se déroulent aujourd’hui la grande majorité des transactions – semble tenir bon. En réalité, c’est à ce niveau-là que se sont amorcés les changements dans les habitudes d’achat.

Aujourd’hui les salles de vente ne représentent plus que 45% des échanges commerciaux à l’échelle globale, le reste se faisant via les marchands. A vrai dire, ces ventes aux enchères peuvent s’avérer intimidantes pour les acheteurs inexpérimentés, et si par malheur les offres n’atteignent pas le prix de réserve, le vendeur risque même de ne pas réaliser de vente du tout.

Les galeries s’appuient de plus en plus sur les foires, où l’art peut être vu par un plus large public. Art Basel (16-20 juin, artbasel.com) et Design Miami/Basel (15-19 juin, designmiami.com) sont les deux rendez-vous incontournables de l’agenda estival des collectionneurs, mais en fin de compte, il se passe rarement une semaine sans qu’une foire ne s’ouvre quelque part. Et si un jour, dans une de ces foires vous tombez sur une oeuvre qui vous touche, regardez-la bien, car ce sera peut-être la dernière fois qu’elle sera exposée en public. Mieux encore, achetez-la. Le marché est fluctuant, certes, mais la beauté, elle, peut s’avérer une source de joie éternelle.

NL Het prijskaartje van kunst

De kunstmarkt heeft flinke klappen gekregen tijdens een van de ergste recessies die Europa ooit heeft doorgemaakt. Maar nu het vertrouwen van de kopers stilaan terugkeert, liggen er misschien opnieuw mooie tijden in het verschiet. Claire Wrathall schuimt de markt af voor meer details.

Toen een anonieme koper in februari in Sotheby’s in Londen € 72 miljoen betaalde voor Giacometti’s L’homme qui marche I, ging er een zucht van opluchting door de kunstwereld. Dit moment, samen met de indrukwekkende verkoopsresultaten van hedendaagse kunst via Sotheby’s, was het bewijs dat de markt een bladzijde had omgeslagen.

Het jaarverslag van TEFAT, de grootste internationale jaarlijkse kunstbeurs, bracht nog meer redenen voor optimisme. Het toonde aan dat, hoewel sommige sectoren van de markt te lijden hadden onder de recessie, andere sectoren – waaronder oude meesters, juwelen en vooral Chinese kunst – het veel beter hadden gedaan dan voorspeld. En het allerbelangrijkste nieuws was dat het onderste deel van de markt – waar tegenwoordig de meeste transacties gebeuren – het blijkbaar goed blijft doen.

Dat nieuws heeft een verandering veroorzaakt in de manier waarop mensen kunst kopen. Het aandeel van veilingen in de totale verkoopcijfers is gedaald tot 45%. De rest van de verkopen gebeurt via handelaars. Veilingen kunnen tenslotte intimiderend overkomen voor onervaren kunstliefhebbers. En als verkoper ben je er niet zeker van of je wel iets zult verkopen als de minimumverkoopprijs niet gehaald wordt. Handelaars vertrouwen meer en meer op beurzen, waar over het algemeen veel meer mensen de kunstwerken te zien krijgen. Art Basel (16-20 juni, artbasel.com) en Design Miami/Basel (15-19 juni, designmiami.com) zijn twee afspraken voor de zomer die elke verzamelaar met stip in zijn agenda heeft genoteerd. Er gaat haast geen week voorbij zonder dat er ergens een beurs plaatsvindt. Als je op een beurs een knap kunstwerk vindt, neem het dan nog even goed in je op, want de kans is groot dat het voor het laatst in het openbaar te zien is. Of beter nog: koop het zelf. Markten kunnen fluctueren, maar van prachtige kunst kan je eeuwig genieten.

Leave a Reply