Inflight Magazine of Brussels Airlines

Welcome to the Inflight Magazine of Brussels Airlines

The spirit of Gascony

First distilled 700 years ago, Armagnac remains as enigmatic and under-appreciated as the region in southwest France in which it’s produced. Morwenna Ferrier drinks to Gascony’s unspoilt beauty

IMAGE 4CORNERS CORBIS, PHOTOLIBRARY.COM

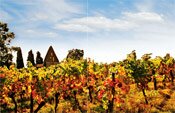

In Gascony, ducks outnumber people by 20 to one. This vine-shaped region, plump with hills and plum trees, is incongruously untouched by man, which is remarkable for many reasons. First, there’s its location, wedged between the resort of Biarritz and the chattering classes of Provence. Then there’s the warm, breezy climate. From an aesthetic point of view, Gascony is pretty in a uniquely rugged way, with vines, prunes and requisite sunflower fields. Finally, it offers what is possibly the cheapest and finest food and wine in southern France. What’s not to like? I ponder this question as I begin my journey from Toulouse, via Auch, Condom and Eauze, to discover this region’s equally mysterious spirit.

In Gascony, ducks outnumber people by 20 to one. This vine-shaped region, plump with hills and plum trees, is incongruously untouched by man, which is remarkable for many reasons. First, there’s its location, wedged between the resort of Biarritz and the chattering classes of Provence. Then there’s the warm, breezy climate. From an aesthetic point of view, Gascony is pretty in a uniquely rugged way, with vines, prunes and requisite sunflower fields. Finally, it offers what is possibly the cheapest and finest food and wine in southern France. What’s not to like? I ponder this question as I begin my journey from Toulouse, via Auch, Condom and Eauze, to discover this region’s equally mysterious spirit.

The French lost a lot of their Armagnac during the Second World War. The evaporated alcohol from the barrels would turn store rooftops black, so German bombers would fly over Gascony looking for such signs of distilling before pillaging the barrels. Evidently the spirit survived, however, and I observe it flowing freely as I plan my route over a drink in Le St Jerome cocktail bar on Rue St Antoine du Toulouse, where the bona fide BCBG (bon chic bon genre) of Toulouse partake in aperitifs. It’s in bars like these that Armagnac, in a bid to modernise, is attempting to buck up its status as a spirit to be mixed, rather than merely drunk by the aristocracy. Yes, that’s right – Gascony’s eau de vie wants to be rebranded as a rival to Bacardi.

Local heroes

Local heroes

Driving west from Toulouse, the land undulates, then goes flat, much like the Netherlands, before dipping sharply down on narrow roads flanked by large masses of Scandinavian-like woodland. The only indication of its Franco personae are the ubiquitous signs asking me to sample one of the Gers’ famous foodstuffs: foie gras, vins du pays and, of course, Armagnac.

Armagnac is made from any one of 11 different grapes, but ugni blanc, colombard, baco and folle blanche are the most common varieties. These are grown in three Armagnac-producing regions in Gascony: Haut-Armagnac, Bas-Armagnac and Ténarèze. With varying degrees of sand and clay in their soil, production is very weather dependent. Harvest begins in late September and can go on until Christmas, but it’s at distillation time when you really see how much this drink is absorbed into the local culture. Known as ‘La Flamme de l’Armagnac’, there are hundreds of events built around it, in particular celebratory dinners set around the giant copper alembics that are used for distilling. Locals feast on innards, foie gras and duck while the alembics chug away, producing the next year’s vintage.

Drink to history

Drink to history

In the heart of the Bas-Armagnac sub- region, near Condom, lies Château du Busca-Maniban. A magnificent Louis XIV château perched on a ridge at one of the region’s highest points, Armagnac has been produced here since 1649, and the outhouse rooftops are still dark from storing it. I ask owner Floriane de Ferron, one of Armagnac’s last indomitable female producers, about the future of the spirit. It doesn’t sound like good news. “In three years’ time, there will be little or no subsidies and the price of crops will get to a point where no farm can continue,” she says. “The vines will go and, I fear, so will Armagnac; 2009 was a bad year – just four barrels were filled.”

Busca-Maniban’s wine and Armagnac vineyards face different directions, but from the back of the château, where the winds are strong and the sun is high, they appear otherwise identical, demarcated by a single crumbling dovecote. With Gascony’s precarious weather – relentless heat and an inordinate amount of rain – crop failure is rife. I can see patches that are shaved clean of vines, a reminder of how financially perilous a multi-temperate region can be. Barrels alone cost around €700 each, so once the 40% tax is added, a good year will see producers just breaking even; de Ferron lost €300 per hectare last year. Still, the multi-coloured fungi on the floor of the barn are apparently a promising indication for 2010.

Variable vintages

Variable vintages

Armagnac is distilled from fermented grape juice. The grapes are initially treated much like wine, but once fermented, the low-alcohol liquid is heated in the alembic. The clear alcohol is then aged in oak barrels before being bottled as a vintage. Each varies with staggering degrees, and can repulse or delight. Busca-Maniban’s 1985 won medals, while 1973 is like drinking bitter velvet prunes. The year after has notes of orange, but novices like myself may find they lean towards the recent vintages, which are the easiest to swallow.

The high tax, along with a desire to actually participate in their retirement, led Dutch couple Joop and Marijke Schleicher to rent out their vineyards. I spend a few nights camping at their spectacular purpose-built garden campsite near the medieval village of Castelnau d’Auzan. Joop keeps the remnants of what was once distilled in his multi-padlocked barn beside their house. He guides me to a solitary oak barrel to taste his Armagnac – a peaty, winch-inducing drink that warms the soul. This is something to be proud of, I say. He laughs: “It’s good, but I’ll never go back to it. Producing this almost killed me.”

Acquired taste

Acquired taste

I spend the second half of the week near Eauze, in a gîte owned by Jackie and Richard Wallace-Jones. Their converted barns fit neatly in the quietude between cycling pitstop Demu and Eauze itself. It’s raining as we meet, and I ask Jackie whether the climate has played a part in the region’s lack of tourists. “It’s changeable,” she agrees, “but believe me, it’ll be glorious soon. I think it’s the tourist board who don’t want to promote it.” And why not salvage one corner of France to keep for themselves?

Later I ask Amanda, who runs the Armagnac tourist office, whether Gascony’s divisive food might deter visitors. We’re having lunch in Condom, at the Michelin- starred La Table des Cordeliers. “It’s quite hardcore I suppose,” she admits, “but that aside, this is brilliant, foodie food.” I agree, as we tuck into the market menu: a five-course feast that includes foie gras done three ways. I do quail at the prospect of a platter of seared sweetmeats (testicles), however, and wonder whether it’s locals or tourists who eat this on daily basis.

At the end of my trip, I conclude that Gascony is France minus the sugar coating – and that Armagnac remains at its heart, metaphorically and geographically. Quite how its produce is so overlooked remains a mystery. An Armagnac producer at Château de Cassaigne in Haut-Armagnac has seen fit to produce Cassagnac – an Armagnac version of Bailey’s – in an attempt to attract new punters. I hope it succeeds, but until then I’m perfectly happy to enjoy this region of France without the tourist hordes.

FR L’eau-de-vie de Gascogne

Distillé depuis 700 ans, l’Armagnac reste aussi énigmatique que sa région d’origine. Un récit de Morwenna Ferrier

J’ai commencé ma découverte de l’Armagnac en prenant un verre au bar St Jerôme, à Toulouse. C’est dans ce genre de bar à apéritifs branché que l’eau-de-vie gasconne tente de se forger une nouvelle image. Fini la boisson de l’aristocratie, vive les nouveaux cocktails mélangés !

L’Armagnac est produit à partir d’une palette de 11 cépages, tous différents les uns des autres, cultivés dans le Haut-Armagnac, le Bas-Armagnac et le Ténarèze. Au Château du Busca-Maniban dans le Bas-Armagnac, par exemple, on le produit depuis 1649. Mais avec son climat variable, la Gascogne connaît souvent des pertes de récoltes. Selon la propriétaire Floriane de Ferron, « 2009 fut une mauvaise année (…). » Quand on voit le coût d’un fût, lors d’une bonne année, les producteurs rentrent à peine dans leurs frais.

Le goût varie aussi énormément. Une fois fermenté, le vin est distillé dans un alambic en cuivre, avant d’être mis à vieillir dans des fûts de chêne. Chaque millésime peut soit déplaire soit séduire. En 1985, le Busca-Maniban a remporté des médailles, alors qu’en 1973, il avait un goût de prunes amères. C’est clair, produire de l’Armagnac ne se fait pas sans peine.

Visiter la Gascogne non plus d’ailleurs : avec son temps variable et sa cuisine tout en contrastes – comme le foie gras et les douceurs – cette destination n’est pas un choix facile pour les visiteurs. Mais la Gascogne, c’est la France – et l’Armagnac est au cœur de cette région. En attendant que sa renommée ne dépasse les frontières, je suis heureuse de le déguster, loin du flot des touristes.

NL De geest van Gascogne

Morwenna Ferrier ontdekt hoe Amagnac, 700 jaar geleden voor het eerst gebrouwd, al even enigmatisch blijft als de streek waar het wordt geproduceerd

Ik start mijn dag met het bekende drankje uit Gascogne in de cocktailbar St Jerome in Toulouse, waar het trendy stadsvolkje naartoe trekt voor een aperitief. In dit soort bars probeert Armagnac zich te profileren als het ideale drankje voor een cocktail dat niet louter wordt genuttigd in aristocratische kringen.

Armagnac wordt vervaardigd uit een 11-tal verschillende druivensoorten die worden geteeld in de Haut-Armagnac, Bas-Armagnac en Ténarèze. In het Château du Busca-Maniban in de Bas- Armagnac wordt sinds 1649 Armagnac gebrouwen. Maar het wisselvallige klimaat van Gascogne doet de oogst vaak mislukken. Volgens eigenaar Floriane de Ferron was 2009 een slecht jaar (…). Rekening houdend met de kosten voor een vat en 40% belastingen zullen de producenten met een goed jaar net break-even halen.

De smaak varieert eveneens enorm. Zodra de laagalcoholische vloeistof fermenteert, wordt ze opgewarmd in een koperen distilleerkolf om daarna te rijpen in eikenhouten vaten. Een oogst kan mislukken of slagen. Zo sleepte een Busca-Maniban uit 1985 talrijke medailles in de wacht, terwijl die uit 1973 naar bittere pruimen smaakt. Armagnacproducenten oogsten geen eenvoudig succes.

Misschien kan hetzelfde worden gezegd van Gascogne; met zijn veranderlijk klimaat en uiteenlopende gastronomie zoals foie gras en snoepgoed is het geen voor de handliggende toeristenbestemming. Maar Gascogne is Frankrijk zonder zijn zeemzoete laag – met Armagnac als aandachtstrekker. Zolang zijn aantrekkingskracht nog niet alomgekend is, geniet ik graag van deze streek - zonder de toeristen.

Leave a Reply