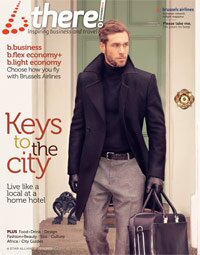

Inflight Magazine of Brussels Airlines

Welcome to the Inflight Magazine of Brussels Airlines

Tasting Tel Aviv

With influences stretching from Northern Europe to the Far East, all sorts of flavours go into Tel Aviv’s culinary melting pot. Anthea Gerrie asks local chefs where to go to enjoy deliciously diverse dining

Photography Nitzan Hafner

Given its cosmopolitan origins, it’s no wonder that Tel Aviv is a great city for food. The sheer range of cuisine on offer, however, is greater than you might expect. It will come as little surprise to find the spicy flavours of the Levant colliding with the seafood and fresh produce of the Med. But there’s more to this city’s dining scene than Middle Eastern and Mediterranean cuisine. Immigrants from Poland, Germany, Russia, Bukhara, North Africa, Iraq and the Yemen have brought their own dishes to the melting pot. Futhermore, young Israelis love to bring back Asian recipes from their travels in the Far East to enjoy in their home city.

Given its cosmopolitan origins, it’s no wonder that Tel Aviv is a great city for food. The sheer range of cuisine on offer, however, is greater than you might expect. It will come as little surprise to find the spicy flavours of the Levant colliding with the seafood and fresh produce of the Med. But there’s more to this city’s dining scene than Middle Eastern and Mediterranean cuisine. Immigrants from Poland, Germany, Russia, Bukhara, North Africa, Iraq and the Yemen have brought their own dishes to the melting pot. Futhermore, young Israelis love to bring back Asian recipes from their travels in the Far East to enjoy in their home city.

Indigenous delights

Hummus has been a favourite of Middle Eastern cuisine for 7,000 years, but this Arab dish isn’t ubiquitous in Tel Aviv. “In Israel we so enjoy the tahini – or sesame paste – that goes into hummus that we use it by itself,” says Ronen Skinezes, chef at buzzy beachfront restaurant Manta Ray (Alma Beach, ). “We spice up tahini with lemon juice for a breakfast dip, and mix it with honey to make a halvah-like dessert for dinner.” Between May and October, Manta Ray serves hummus on the beach from a kiosk. At other times, Skinezes heads to the medieval warrens of the old city of Jaffa when he has a hummus craving: “Abu Hassan (1 Dolphin Street, Jaffa, no reservations) is the place… they make it fresh every morning, and when it’s gone, it’s gone.”

Hummus has been a favourite of Middle Eastern cuisine for 7,000 years, but this Arab dish isn’t ubiquitous in Tel Aviv. “In Israel we so enjoy the tahini – or sesame paste – that goes into hummus that we use it by itself,” says Ronen Skinezes, chef at buzzy beachfront restaurant Manta Ray (Alma Beach, ). “We spice up tahini with lemon juice for a breakfast dip, and mix it with honey to make a halvah-like dessert for dinner.” Between May and October, Manta Ray serves hummus on the beach from a kiosk. At other times, Skinezes heads to the medieval warrens of the old city of Jaffa when he has a hummus craving: “Abu Hassan (1 Dolphin Street, Jaffa, no reservations) is the place… they make it fresh every morning, and when it’s gone, it’s gone.”

Olives have also been cultivated here for thousands of years, and Israel makes fine olive oil. A personal bottle is presented to every customer at Raphael (87 Hayarkon street, ), which serves salads of amazingly sweet, small tomatoes cultivated in the Negev Desert.

Israel’s avocados are now as famous as the country’s citrus fruits; look out for them at breakfast, alongside local dairy goodies such as laban (a cross between buttermilk and yoghurt) and soft local cheeses. They’re all laid out to be enjoyed with cucumber, tomatoes and home-grown herbs; the hearty breakfasts once reserved for farmers in the fields are now a firmly established urban tradition.

Mint turns up not only on breakfast buffets but also in the city’s favourite beverage: a combination of green tea and huge handfuls of the bright green leaves, known as ‘nana tea’. Or if you’re after something stronger, Israeli wine was first grown on this territory in Roman times, and is now winning international awards thanks to a new generation of winemakers.

Immigrant eats

Immigrants have brought a plethora of influences, from the cold-weather food of eastern European to the spicy dishes of North Africa. The former includes famous dishes associated with Ashkenazi Jewish cuisine, such as chopped liver, gefilte fish (poached carp dumpling) and chicken soup with kreplach or kneidlach dumplings. These old-fashioned dishes can be hard to find now the spicier dishes of the Sephardic tradition are preferred, but examples are always on offer at the Friday-night buffets that are the pride of the city’s big hotels.

Immigrants have brought a plethora of influences, from the cold-weather food of eastern European to the spicy dishes of North Africa. The former includes famous dishes associated with Ashkenazi Jewish cuisine, such as chopped liver, gefilte fish (poached carp dumpling) and chicken soup with kreplach or kneidlach dumplings. These old-fashioned dishes can be hard to find now the spicier dishes of the Sephardic tradition are preferred, but examples are always on offer at the Friday-night buffets that are the pride of the city’s big hotels.

Moroccan and Tunisian immigrants have made couscous a new Israeli staple, and introduced slow-cooked lamb with olives, prunes or apricots. These communities also lay claim to a local favourite, shakshuka – a dish of eggs sitting in a spicy tomato sauce. It’s found in many breakfast places, but the owner of the joint dedicated to the dish, Dr Shakshuka (4 Beit Eshel Street, Jaffa, ), insists that the recipe originated in Libya.

Also bringing their traditional dishes are immigrants from Iraq (making bulgur wheat into boat-shaped pastries known as kubee, stuffed with meat and fried), Yemen and, most recently, Russia. “The Russians have brought many kinds of dumplings or piroshki, stuffed cabbage and other appetisers,” says Miki Nir, chef at the Dan Panorama Hotel (Charles Clore Park, ). Nir makes these zakuski, as the snacks are known, for his Russian corner on the hotel’s breakfast buffet, and likes to eat Russian food at Baba Yaga (12 Hayarkon Street, ) on his day off. He also employs several Bukharan chefs, saying, “The Bukharans have really enriched our cuisine with all kinds of rice dishes.”

Far East flavours

There may be few indigenous Jews in the Far East, but Israelis travel in droves to India and Thailand, and have imported the cuisines of their favourite holiday destinations to Tel Aviv. Perhaps surprisingly, there is also a local passion for sushi.

There may be few indigenous Jews in the Far East, but Israelis travel in droves to India and Thailand, and have imported the cuisines of their favourite holiday destinations to Tel Aviv. Perhaps surprisingly, there is also a local passion for sushi.

Dishes with a Vietnamese influence appear on the menu at Montefiore (36 Montefiore Street, ) in the area behind Rothschild Boulevard dominated by smart galleries. “But this is only a French colonial influence…” says the restaurant’s CEO Oren Schnabel, “when I want all-out Asian food I go to the Thai House (8 Bograshov Street, ), which is one of the best restaurants in Tel Aviv.” He continues, “When it comes to modern Asian food, Sushi Samba (27 Habarzel Street, ) does a good job, and so does Zepra (96 Yigal Alon, ), which offers fusion cuisine. Asian food has become so popular here because it’s lighter, and the fresh ingredients and spices suit our palates.”

The Montefiore doesn’t serve indigenous food, immigrant fare or pan-Asian cuisine – it’s an original, yet nevertheless one of the finest restaurants in Tel Aviv. And that’s what makes this city such an exciting place to dine; in addition to the myriad influences, there are many restaurants that simply defy definition.

Tel Aviv soul food

Hummus as served on the beach from the Manta Ray restaurant

Ingredients

2 cups dried chickpeas, soaked

overnight in cold water

1/3 cup ice cubes

1/3 cup lemon juice

1/2 cup tahini paste

2 garlic cloves, crushed

1tsp ground cumin

salt

Method Place the chickpeas in a large saucepan with cold water to cover, bring to the boil and cook over a medium heat for one hour until very tender. Drain, reserving 1/4 cup of the cooking liquid. Transfer the chickpeas, reserved cooking liquid and ice cubes to a food processor, add the lemon juice, tahini, garlic and cumin, and whizz until smooth. Season to taste and serve.

FR La table de Tel Aviv

Anthea Gerrie a questionné les chefs locaux sur la délicieuse diversité culinaire de Tel Aviv, véritable fusion de saveurs dans une ville cosmopolite

L’houmous est depuis plus de 7 000 ans un des mets favoris de la cuisine du Moyen-Orient. On le sert au Manta Ray, en bord de plage (Alma Beach, tél. 2 ). Pour le chef, Ronen Skinezes, cet ingrédient se prête à différentes utilisations : « Nous ajoutons du jus de citron au tahini pour en faire une sauce, et du miel pour en faire un dessert. » On cultive également des olives dans la région depuis des milliers d’années, et au Raphael (87 Hayarkon street, tél. 2 ), on offre une bouteille d’huile d’olive à chaque convive.

Les immigrants ont également apporté une kyrielle d’influences. Les Européens de l’Est ont amené des plats de la cuisine juive Ashkenazi, tels la crêpe farcie et la soupe aux boulettes. Les Marocains et les Tunisiens, quant à eux, seraient à l’origine du célèbre shakshuka – des œufs aux tomates épicées – mais le propriétaire du Dr Shakshuka (4 Beit Eshel Street, tél. 2 ) réfute cette idée : la recette vient de Libye. Les immigrants russes ont « introduit les boulettes, le chou farci au riz et autres amuse-gueule, » poursuit Miki Nir, chef à l’Hôtel Dan Panorama (Charles Clore Park, tél. 2 ). Il apprécie le Baba Yaga (12 Hayarkon Street, tél. 2 ).

Enfin, les jeunes Israéliens ont importé les recettes de leurs vacances de prédilection en Extrême- Orient. Des influences vietnamiennes font ainsi leur apparition au menu français du Montefiore (36 Montefiore Street, tél. 2 ), et le CEO Oren Schnabel confie que « lorsqu’il veut une cuisine asiatique à 100%, il se rend à la Thai House (8 Bograshov Street, tél. 2 ). »

NL Aan tafel in Tel Aviv

Anthea Gerrie vraagt plaatselijke chef- koks naar de smakelijkste en gevarieerde culinaire aanraders van Tel Aviv, en proeft van de mengelmoes van smaken in de smeltkroes van deze wereldstad

Hummus heeft al 7000 jaar een prominente plaats in de keuken van het Midden-Oosten. Het wordt aan de kust geserveerd bij Manta Ray (Alma Beach, ), waar chef Ronen Skinezes beweert dat de ingrediënten ook andere doeleinden hebben: “We gebruiken tahini met citroensap als dipsaus en mengen het met honing om een dessert te bereiden.” Ook olijven worden al duizenden jaren lang geproduceerd in de streek. Bij Raphael (87 Hayarkon street, ) krijgt elke klant een fles olijfolie mee naar huis.

Immigranten hebben heel wat invloeden meegebracht. Oost-Europeanen brachten specialiteiten van Asjkenazische joden mee. Marokkaanse en Tunesische inwijkelingen zouden de plaatselijke favoriet shakshuka hebben ingevoerd – eieren met gekruide tomaten – maar de eigenaar van Dr Shakshuka (4 Beit Eshel Street, ) beweert dat het originele recept uit Libië komt. “Russische immigranten introduceerden hartige meelballetjes, gevulde kool met rijst en andere hapjes”, zegt Miki Nir, chef van het Dan Panorama Hotel (Charles Clore Park, ). Hij is een fan van Baba Yaga (12 Hayarkon Street, ). Jonge Israeli, ten slotte, brachten de geneugten van hun geliefkoosde vakanties in het Verre Oosten mee. Dat leidt tot Vietnamese invloeden op het Franse menu van Montefiore (36 Montefiore Street, ), en CEO Oren Schnabel zegt: “Als ik trek heb in Aziatische specialiteiten, ga ik naar het Thai House (8 Bograshov Street, ).”

Leave a Reply